Climate change could be contributing to rise of a potentially deadly fungal pathogen

The emergence of a partially drug-resistant fungal infection in Canadian hospitals and elsewhere has doctors and scientists scrambling to understand the pathogen and stop its spread.

Candida auris was virtually unknown until 2009, but the past decade has seen outbreaks of infection in hospitals and long-term care facilities around the world, predominantly among patients with weakened immune systems, such as people receiving chemotherapy or surgery and those who receive medication through large intravenous lines.

So far C. auris remains relatively rare, said Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease physician at Toronto General Hospital. But the fungus, which can cause infections, including of the blood, of wounds and ears, has three main features that make it worrisome to health-care professionals:

- It’s tricky for some laboratories to identify.

- It can be hard to treat successfully when it invades the bloodstream.

- It’s frequently resistant to one or more classes of antifungal medications that doctors turn to first.

“It poses a bit of challenge to treat, and the reason is there can be delays in diagnosis: conventional labs might not be able to detect that it’s Candida auris right away,” said Bogoch.

“With the delayed diagnosis, that can often delay appropriate treatment — and if we delay treatment for fungal infection, especially when they’re in the blood, people can get very sick, very quickly.”

Serious infection

In Canada, provincial laboratories and the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg are able to identify the specific infection. In the developing world, detection isn’t always possible, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Symptoms may not be noticeable because patients with C. auris infection are often already sick in the hospital.

Based on information from a limited number of patients, the CDC estimates more than one in three patients with invasive C. auris die.

Canada has had a total of 20 cases of C. auris from 2012 to June 2019, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) said:

- 6 cases in Central Canada (Quebec or Ontario) between 2012 and 2017.

- 14 cases in Western Canada (Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta or British Columbia) between 2014 and June 2019.

Canada’s first case of multidrug-resistant C. auris was diagnosed in July 2017, imported by a returning traveller, said PHAC spokesperson Anna Maddison.

Some — but not all — of the resistant infections were acquired in hospitals outside Canada, Maddison said. It’s not known how the others acquired it.

“We absolutely will be seeing more cases,” Bogoch said.

Why C. auris started spreading widely after it was first spotted a decade ago in the ear of a patient in Japan remains a mystery. (Auris means ear.)

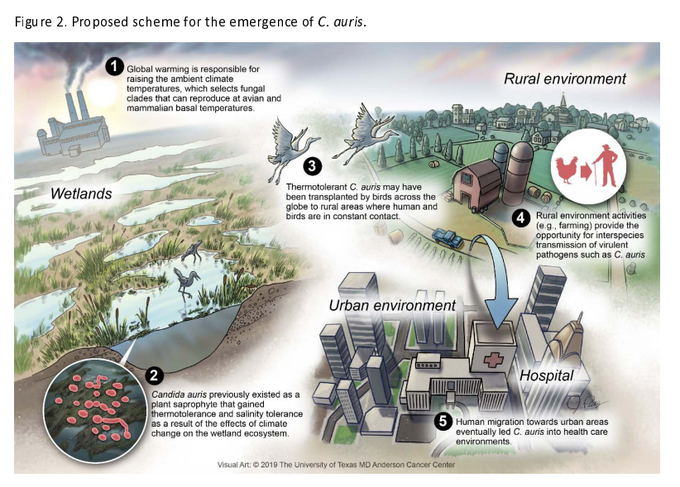

Dr. Tom Chiller, chief of the CDC’s Mycotics Diseases Branch, and his colleagues set out to understand its origins, and documented their findings in a commentary published earlier this month in the Journal of Fungi.

To find some clues, Chiller’s team peered into the genome of C. auris and related species, and mapped where its been detected in hospitals globally.

To follow another lead in the investigation, Dr. Arturo Casadevall and his colleagues compared C. auris to some its closest relatives in the laboratory and found the pathogen is more resistant to heat and grows at higher temperatures.

Body temperature no barrier

Our normal body temperature of 37 C prevents most fungal species from replicating. But C. auris’s genome showed that it has adapted to higher temperatures, said Casadevall, chair of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. That heat tolerance could contribute to its emergence as a fungal disease in humans.

Casadevall and his colleagues at the University of Texas in Houston and Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute in Utrecht, Netherlands, suspected the world’s warming climate could be contributing.

They brainstormed for a common denominator to explain C. auris’s “mystifying” appearance in three very different regions of the world with distinct flora and geographic conditions: South Africa, South America and India.

‘Looming problem’

“The big picture here, the concern here is that as the planet gets warmer, more of these [fungal] organisms that currently are not a threat may adapt to the higher temperatures,” Casadevall said. “It’s a looming problem.”

He put together the genetic evidence with the conjecture in what the American Society for Microbiology called an opinion/hypothesis paper titled “On the emergence of Candida auris: Climate change, azoles [an antifungal agent], swamps and birds.” It was published in this week’s issue of the society’s journal mBio.

CDC’s Chiller said several factors may be contributing to the emergence of C. auris, including:

- Expansion of industrial farming.

- Warmer temperatures.

- Changes to the fungus itself.

“We don’t know what role the environmental changes are playing in this emergence. However, we do know that fungi are very susceptible to changes in the environment and would want to understand better what effects changes have in this and other species,” Chiller said in an email in response to Casadevall’s paper.

Chiller’s team also speculated about the roles of health care, antifungal use and human activities in helping C. auris spread.

On the emergence of Candida auris: climate change, azoles, swamps and birds – Arturo Casadevall et al. – bioRxivhttps://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/657635v1.abstract …

For infectious disease physicians, hospital outbreaks are a concern given the fungus’s other unique characteristics, such as tolerance of hypersaline conditions and the ability to lurk on dry surfaces like bed railings.

Even after a C. auris infection is treated, patients might continue to carry it on places like their skin without it causing illness. They can still spread it to other patients if precautions aren’t taken.

That’s why public health and infectious disease experts say measures such as hand hygiene and wearing gloves, placing patients with C. auris in a single-patient room, and cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in hospital rooms as well as on mobile equipment such as temperature probes and nursing carts will control the spread.